Cambodia's Capacity Crisis: Overcrowded Prisons and the Need for Reform

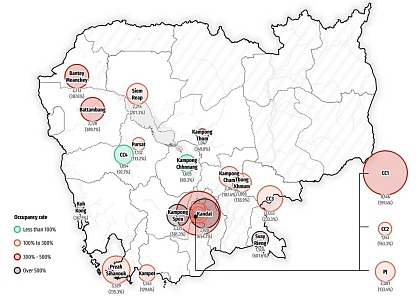

Published on 18 February 2025In 2010, LICADHO reported that Cambodia’s prisons were experiencing an unprecedented population boom. The prisons monitored by LICADHO were at 175% capacity, and projections indicated that by 2018, the country could have one of the most overcrowded prison systems in the world.

Fifteen years later, Cambodia’s prisons remain as overcrowded and under-resourced as ever. Data from the World Prison Brief positions Cambodia as having the second highest prison occupancy level in the world as of July 2023. At the end of 2024, 18 of the 19 prisons monitored by LICADHO exceeded their official capacity, with 11 prisons at an occupancy rate of at least 200%. These prisons hold over 45,000 individuals combined: a 23% increase from December 2023. Kandal Prison is currently the most overcrowded facility, holding over 3,900 people in a space designed for only 600, rendering its occupancy rate over 650%.

Kandal Prison is currently the most overcrowded facility, holding over 3,900 people in a space designed for only 600, rendering its occupancy rate over 650%.

Several government officials, including representatives from the General Department of Prisons (GDP), have publicly acknowledged the issue of overcrowding and proposed reforms, such as increasing the capacity of some facilities. However, the way in which prison infrastructures have already been adjusted has only intensified the issue. For instance, Kampot Prison was recently reconstructed to boost its official capacity from 200 to 1,200, which included the construction of structures to divide existing cells into two floors. These two-storied cells exacerbate the already cramped and unhygienic living conditions for people in prison and increase the likelihood of contracting air-borne and communicable diseases. These steps fall woefully short of addressing systemic issues: Cambodia cannot simply build its way out of the overcrowding crisis.

The GDP does not control how many people its prisons receive. Key players in criminal justice reform – such as the Ministry of Justice, prosecutors and the courts – have yet to implement serious reforms. Alternatives to detention, including the utilisation of bail procedures, remain direly underused. In December 2024, approximately 75% of people detained in prisons monitored by LICADHO were in pre-trial detention, having yet to be convicted of a crime or awaiting a final judgement. The government is doing little to reduce the justice system’s reliance on incarceration as the default response to those accused of violating the law.

More effective measures are clearly needed to drastically reduce Cambodia’s ever-growing prison population. LICADHO calls on authorities to immediately address this ongoing crisis and:

▪ Limit pre-trial detention to a measure of last resort as required by law;

▪ Grant bail to all eligible persons, particularly minors, pregnant individuals, and mothers detained with young children;

▪ Utilise alternatives to detention (such as diversion programs), particularly for non-violent drug offenses, and consistently utilise these measures in future cases;

▪ Implement measures for the early, temporary, or conditional release of individuals convicted of misdemeanours or non-violent offenses, and focus on those nearing the end of their sentences and at-risk groups (such as older people and pregnant individuals);

▪ Immediately release all people held without a sufficient legal basis, including all those arbitrarily detained in compulsory drug detention centres;

▪ Take steps to establish the infrastructure necessary to implement non-custodial sentences on a broad scale. These steps could include: the training of judges, prosecutors, defence lawyers and all other court staff on the proper use of non-custodial sentences; and the development of a probation department or similar government office dedicated to the supervision and rehabilitation of non-custodial offenders;

▪ Improve prison conditions to ensure every detained person has access to adequate nutrition, healthcare, family visits, and age-appropriate development opportunities; and

▪ Ensure the United Nations Standard Minimum Rules for the Treatment of Prisoners (the ‘Nelson Mandela Rules’) and the United Nations Rules for the Treatment of Women Prisoners and Non-custodial Measures for Women Offenders (the ‘Bangkok Rules’) are adhered to so as to promote the dignity, safety, and wellbeing of all people deprived of their liberty.

MP3 format: Listen to audio version in Khmer

- Topics

- Prison/Detention